Cook Islands Trusts

A Cook Islands trust is a legal structure that places assets beyond the reach of domestic courts by transferring them to a foreign jurisdiction. The Cook Islands does not recognize U.S. judgments or court orders, and it requires creditors to prove fraudulent transfer beyond a reasonable doubt.

No creditor has successfully recovered assets from a Cook Islands trust through Cook Islands court proceedings in more than three decades of contested litigation. When creditors cannot recover, they often settle or abandon collection entirely.

Cook Islands trusts are the most widely used offshore asset protection trust structure, but they are expensive to establish, require ongoing U.S. tax reporting, and add administrative complexity that simpler structures avoid.

Whether someone needs a Cook Islands trust depends on whether their liability exposure and non-exempt asset level justify the cost. Many of the claims that circulate about these trusts, particularly regarding tax benefits, total immunity, and secrecy, are wrong.

Speak With a Cook Islands Trust Attorney

Jon Alper and Gideon Alper design and implement Cook Islands trusts for clients nationwide. Consultations are free and confidential.

Request a Consultation

How a Cook Islands Trust Works

The first step to setting up a Cook Islands trust is to transfer assets to a licensed trustee company. The trustee holds legal title to the assets and administers them in accordance with the trust deed.

The settlor typically remains a beneficiary, but distributions are at the trustee’s discretion. The trustee may make payments to the settlor, but is not legally required to do so. In practice, the trustee almost always follows the settlor’s requests.

The most important feature of a Cook Islands trust is called a duress clause. The duress clause prevents the trustee from complying with the settlor’s requests when they are made under court pressure.

In these situations, the settlor can truthfully tell a U.S. court that they lack the legal authority to comply with a repatriation order. The trustee holds that authority and is governed by Cook Islands law, not U.S. court orders.

Legal Framework

A U.S. judgment has no legal effect in the Cook Islands. The Cook Islands International Trusts Act provides that no foreign judgment is enforceable if it is based on any law inconsistent with the Act. A creditor who wins in a U.S. court must file a new proceeding in the Cook Islands and relitigate the claim.

In the Cook Islands, the burden of proof for fraudulent transfers is beyond a reasonable doubt. That standard is far harder to meet than the preponderance-of-evidence standard used in U.S. fraudulent transfer cases.

Filing deadlines are short. The law requires a claim to be filed within one year of the trust being funded or within two years of the creditor’s claim first arising, whichever is shorter. After those periods expire, the Cook Islands courts will not hear the claim. Each transfer to the trust starts its own clock.

Structure

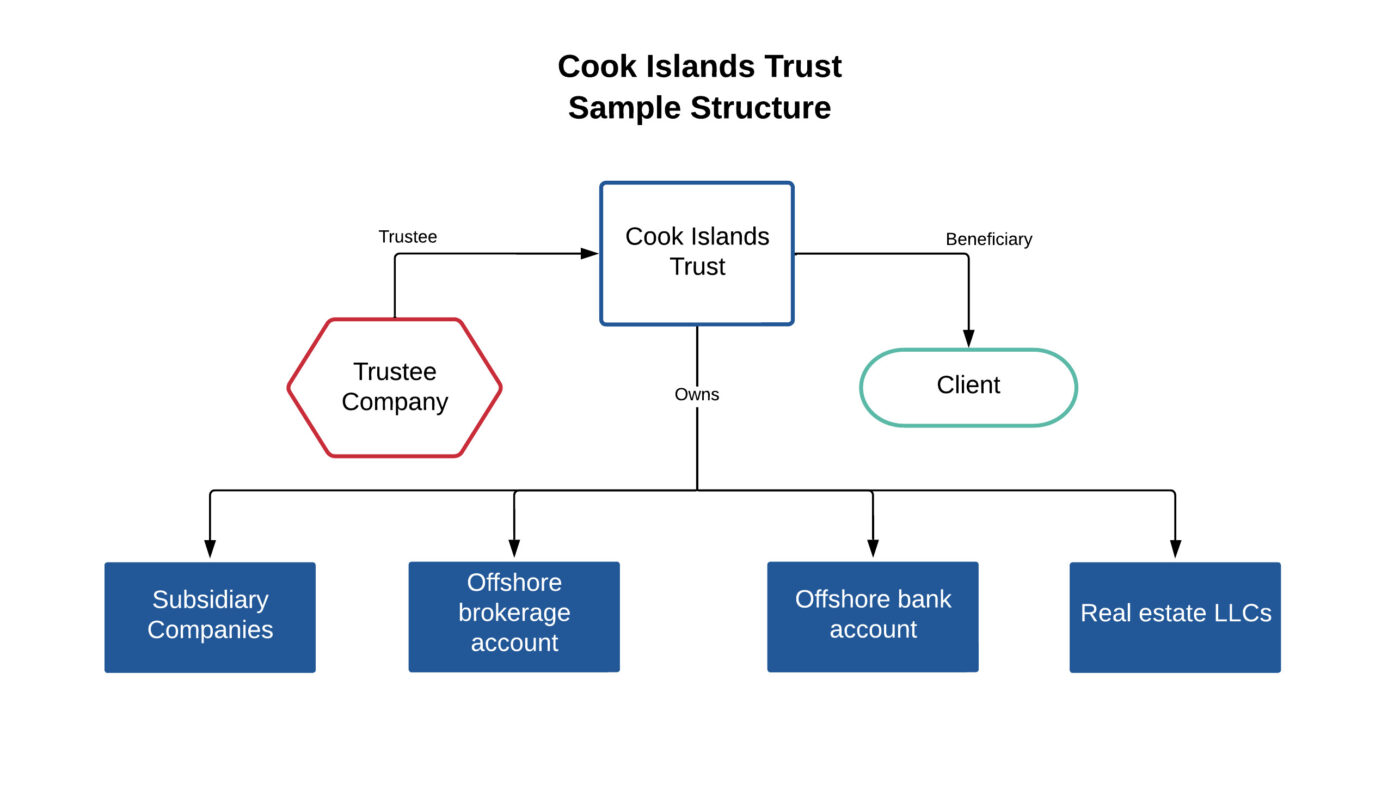

There are two ways to structure a Cook Islands trust: (1) use a trust alone or (2) use an LLC holding company.

When using a holding company, the trust does not hold assets directly. Instead, the trust owns an offshore LLC, and the LLC holds bank or brokerage accounts where the actual assets are kept. The settlor is appointed as the LLC’s initial manager, retaining practical day-to-day control over investments under normal circumstances.

Roles

Every Cook Islands trust has a settlor, a trustee, and a beneficiary. The trust deed defines each party’s role, the defensive provisions that activate when the trust is challenged, and the rules the trustee operates under.

The settlor creates the trust and transfers assets to it. The trustee is a licensed Cook Islands trust company that holds legal title to the assets and administers them according to the trust deed. The beneficiaries are the individuals entitled to benefit from the trust, typically the Settlor and their family.

The mechanics of trust administration—distributions, withdrawals, and ongoing trustee coordination—determine whether the structure runs smoothly or creates friction that leads to costly mistakes.

Setup

Setting up a Cook Islands trust involves four steps:

- Select a licensed Cook Islands trust company to serve as trustee;

- Complete a KYC background check required by anti-money laundering laws;

- Have your U.S. attorney draft the trust deed;

- Fund the trust with cash, investments, business interests, or real property.

It takes three to eight weeks to set up and fund a Cook Islands trust. The time to set up a Cook Islands trust depends heavily on how quickly trust application materials are assembled and submitted.

Establishing a Cook Islands trust during active litigation is possible, but it is not effective for protecting real estate.

Advantages

There are three key advantages to a Cook Islands trust: (1) strong protection from civil judgments, (2) a favorable statute of limitations law, and (3) insulation from political risks.

Protection from Civil Judgments

The main advantage of a Cook Islands trust is its ability to protect assets from civil judgments.

A creditor who wins a judgment in a U.S. court cannot enforce it directly against trust assets. The creditor must pursue assets in the Cook Islands, which does not recognize U.S. judgments or court orders. In this way, a Cook Islands trust provides a second protective layer behind insurance and state exemptions.

A Cook Islands trust can also protect against divorce. A U.S. court can order equitable distribution of marital assets, but it cannot compel a Cook Islands trustee to comply. The trustee operates under Cook Islands law, not U.S. family court jurisdiction, and will not distribute trust assets to satisfy a foreign divorce judgment.

When both spouses own community property, setting up a Cook Islands trust while married requires spousal consent and careful structuring to avoid creating grounds for a fraudulent transfer challenge.

Favorable Statute of Limitations

Once a settlor transfers assets into a Cook Islands trust, a creditor has a very short window to file a fraudulent transfer claim:

- 2 years from the date of transfer; or

- 1 year from the date the lawsuit cause of action arose (if the transfer happened within that 2-year window).

Once the statute of limitations expires, a creditor cannot successfully unwind a fraudulent conveyance in the Cook Islands.

Insulation from Political Risks

A Cook Islands trust can remove assets from the country where the settlor lives. People who are concerned with the political climate of the United States or their home country can use the trust protect their assets from such risks.

Disadvantages

There are three main disadvantages to forming a Cook Islands trust:

- Limited legal protections against trustees. Cook Islands trusts are governed by Cook Islands law, which differs from U.S. law in both procedure and remedies. If a dispute arises, beneficiaries may need to enforce their rights in Cook Islands courts, hire local counsel, and navigate unfamiliar rules.

- High costs. Establishing a Cook Islands trust costs more than a U.S. trust. In addition to legal fees, there are annual trustee fees, banking or custodial costs, and ongoing administration. The costs make it impractical for people with less than $300,000 to protect.

- Limited Control. A Cook Islands trust prevents a settlor from directly controlling the trust assets. Even when using an underlying LLC, the settlor must still involve the trustee when making contributions to and withdrawals from the trust.

Limitations

Cook Islands trusts offer strong creditor protection but do not reduce taxes, eliminate U.S. reporting obligations, or shield assets from disclosure in legal proceedings.

The IRS treats a Cook Islands trust as a grantor trust, which means the IRS looks through the trust entirely. All income, gains, and deductions flow through to the settlor’s personal return. The settlor pays the same taxes as if the assets were held directly. Anyone suggesting otherwise is either mistaken or selling something illegal.

A Cook Islands trust does not eliminate reporting obligations. U.S. persons must file Forms 3520 and 3520-A annually and report foreign financial accounts on the FBAR (FinCEN Form 114). Form 8938 applies when specified foreign financial assets exceed the applicable threshold. Penalties for non-compliance are severe. The compliance obligations for a Cook Islands trust are entirely driven by U.S. law, and the filing requirements apply each year, regardless of whether the trust generates income or makes distributions.

Using a Cook Islands trust does not make assets disappear. It must be disclosed on tax returns, in discovery proceedings, and in response to lawful court inquiries. Attempting to conceal a Cook Islands trust is illegal and counterproductive.

Finally, a Cook Islands trust does not guarantee immunity from contempt. A U.S. court can hold the settlor in contempt for failing to comply with a repatriation order, even if the trustee independently refuses to release the assets.

Costs

A Cook Islands trust costs more to establish and maintain than any domestic planning alternative. First-year costs include $15,000 to $20,000 in legal fees and $3,500 to $5,000 in trustee fees.

Ongoing annual costs include $3,300 to $5,000 in trustee fees, $2,000 to $3,000 in U.S. tax preparation for the required foreign trust returns, and custodial fees charged by the offshore bank or brokerage.

The cost structure varies based on asset complexity, the number of entities involved, and whether situational expenses arise, such as trustee intervention during litigation.

Funding

A Cook Islands trust can hold a wide range of assets, but the mechanics of transferring different asset types into the structure vary significantly.

Cash and securities are the most straightforward to transfer. The trust or its LLC opens an offshore bank or brokerage account, and assets are moved by wire transfer or account transfer. The settlor can typically continue to manage the investment portfolio through the LLC during normal circumstances.

Real estate cannot be moved offshore in the same way. Instead, property is transferred to a Cook Islands trust by assigning an LLC that owns the property to the trust. However, the land remains within U.S. court jurisdiction, which limits the protection.

In general, LLC and business interests can be transferred by assigning membership interests to the trust. Settlors who own operating businesses or investment entities commonly place the equity beyond the reach of creditors while retaining management control through the LLC structure.

Cryptocurrency presents unique challenges in custody, valuation, and compliance. The trust can hold digital assets, but the custodial arrangements and reporting obligations differ from traditional financial accounts.

Each asset type has specific transfer mechanics, documentation requirements, and potential pitfalls. The funding process for a Cook Islands trust is where many structures lose their protective value due to errors in titling, account registration, or timing of compliance.

Cook Islands Trusts vs. Other Jurisdictions

The Cook Islands has the longest track record and the most developed body of case law of any offshore trust jurisdiction. Other jurisdictions commonly compared to the Cook Islands include Nevis, Belize, the Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, and Panama, as well as domestic asset protection trust states such as Nevada, Delaware, and South Dakota. The comparisons across jurisdictions turn on how each balances statutory protections, trustee quality, litigation history, and cost.

No single statutory provision accounts for the Cook Islands’ advantage. Several jurisdictions have modeled their laws on the Cook Islands framework. The difference lies in the combination of tested case law, a trustee market with multiple licensed trust companies, and a judiciary that has consistently upheld the ITA’s protective provisions over more than three decades.

On the other hand, domestic asset protection trusts operate within the U.S. legal system. They remain subject to the Full Faith and Credit Clause, federal bankruptcy jurisdiction, and the power of U.S. courts to compel domestic trustees. A Cook Islands trust operates entirely outside that system.

Ongoing Management

A Cook Islands trust requires active management throughout its life. The trustee monitors trust activity, maintains compliance files, and carries out its duties under Cook Islands law. The settlor must coordinate with U.S. tax advisors for annual filing obligations and with the trustee for any transactions involving trust assets.

The most common problems are mundane: delayed filings, informal side agreements between the settlor and the trustee, and failure to properly document the trustee’s decisions. These administrative failures gradually weaken the trust’s protection and become apparent only when the structure is tested in litigation.