Florida Special Needs Trust Legal Guide

A special needs trust in Florida describes any trust that includes provisions designed to protect a physically or mentally disabled trust beneficiary’s eligibility for need-based government benefits such as Medicaid or Supplemental Security Income (“SSI”). These trusts include restrictions on how funds may be used so that distributions are not made to pay for items that are otherwise provided exclusively from government assistance programs for which the trust beneficiary may qualify.

Medicaid, for instance, has a low ceiling on the amount of a recipient’s countable assets; the limit is approximately $2,200 in Florida (2017). Special needs trusts are designed so that trust assets are not counted for purposes of Medicaid eligibility. The trust agreement typically allows the trustee to distribute income or assets to a beneficiary only if the distribution does not disqualify or diminish a beneficiary’s Medicaid benefit.

While trust assets are not counted for eligibility, trust income can be distributed to improve the recipient’s quality of life by paying for living expenses not covered by Medicaid. Medicaid pays for a disabled recipient’s basic needs such as mortgage payments, rent, food, and utilities. A Florida special needs trust cannot supplant or duplicate Medicaid’s needs assistance. If it does, the trust distributions may disqualify the beneficiary. A special needs trust can supplement Medicaid’s basic benefits by paying for additional care such as:

- Personal grooming

- Clothing and dry cleaning

- Electronic equipment including computers and TVs

- Musical instruments

- Companionship

- Housekeeping and cooking assistance

- Medical insurance and

- Some medical services, therapies, and equipment.

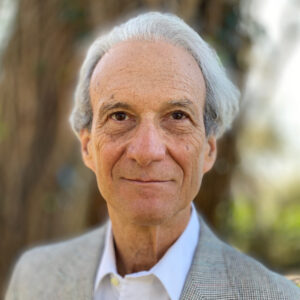

We help families throughout Florida.

Our attorneys can help with your entire estate plan. We can provide all services remotely. Start with a free phone or Zoom consultation.

Florida Special Needs Trust Drafting and Administration

A properly drafted special needs trust should expressly state the trustmaker’s intent to help a beneficiary without affecting the beneficiary’s needs-based eligibility. A special needs trust agreement typically gives the trustee the discretion to distribute to the beneficiary income and principal, provided that the trustee maintains the beneficiary’s eligibility for assistance. The trust agreement tells the trustee that trust assets should be used to supplement but never replace or supplant public benefits. A special needs trust will fail its purpose if the trustee mistakenly uses trust money to duplicate Medicaid benefits such as basic shelter and food.

The Florida special needs trust places much responsibility on the trustee. Suppose the trustee spends money from the trust improperly, such as spending money on basic needs already being paid by Medicaid. In that case, the trustee could cause the beneficiary’s Medicaid benefits to be lost or reduced. The trustee also needs to properly account for trust income taxation. The beneficiary of a special needs trust is liable to pay tax on all trust income even when income is not distributed. Any trustee may be personally liable for improperly administering a Florida special needs trust in a manner that adversely affects the beneficiary’s benefits eligibility.

Disabled beneficiaries are best served by having a professional trustee (accountant, attorney, or institution) serve as trustee of a special needs trust in Florida. Professionals are usually experienced with the responsibilities and liabilities of serving in a fiduciary capacity. They are usually familiar with the regulations applicable to need-based benefit programs such as Medicaid. A professional trustee will usually provide the best use of special needs trust assets for the family member who depends on the assets for Medicaid eligibility.

Third-Party Special Needs Trust

There are two basic types of special needs trusts: (1) third-party trusts established by a beneficiary’s family member and (2) self-settled trusts that the trustmaker creates for their own benefit.

A third-party special needs trust is a trust, or part of a trust, that is created by a third party for the benefit of the Medicaid recipient. In other words, someone other than the beneficiary makes the trust agreement and contributes their own assets to the trust. The third-party who creates these trusts is typically the recipient’s parent or grandparent, and their trust is established as part of the parent/grandparent’s overall estate plan. Often, the parent/grandparent creates a revocable living trust during their lifetime that includes a special needs article.

The special needs article states the trustee shall withhold and retain in the trust any distribution of money that may affect the beneficiary’s benefits eligibility for Medicaid, SSI, etc. The trustee has the discretion to distribute money for supplemental benefits not covered by Medicaid.

Third-party special needs trusts are an important estate planning tool, and they should be included in many family wills or living trusts. A parent/grandparent cannot foresee future changes in their descendants’ health that may result in their need for government assistance to pay for long-term care. No one wants to force a disabled descendant to receive an inheritance that would cause them to forfeit government assistance. If the disabled beneficiary dies without using money held in their third-party special needs trust, the balance of trust assets transfers to the beneficiary’s own heirs and descendants.

One important rule in drafting a third-party special needs trust in Florida is that the trust agreement does not entitle the disabled beneficiary to demand income or principal from the trust. So long as an independent trustee retains the discretion to distribute money from the disabled beneficiary’s trust share, and the trustee follows special-needs directives, the trust assets and trust income should not be counted by Medicaid.

A person may amend their existing will or trust to add special needs provisions. Federal law states that a special needs trust for a surviving spouse can only be created by a will. One cannot use a living trust to create a special needs trust for a spouse. A special needs trust for a child can be established by either will or living trust. There are some ways to draft a living trust-based estate plan that includes special needs protection for a surviving spouse.

Self-Settled Special Needs Trusts

A self-settled special needs trust is a trust established by a person who is disabled and who is an applicant for government support. The support applicant is both the trustmaker and beneficiary. Most provisions of the self-settled trust are like a third-party special needs trust, the most important of which is a restriction against distributions that would eliminate or reduce the beneficiary’s eligibility for Medicaid disability benefits.

People with substantial assets rarely utilize a self-settled special needs trust. Self-settled special needs trusts are typically established by disabled individuals who want to segregate newly acquired assets from Medicaid’s asset eligibility tests. The assets in a properly drafted self-settled special needs trust do not count toward Medicaid’s asset eligibility ceilings.

Often, special needs trusts are used by persons who suddenly receive a significant amount of assets. For instance, if a Medicaid recipient is involved in an accident that results in an insurance claim, the insurance settlement when paid would disqualify the accident victim from needs-based government assistance unless it was held in a self-settled trust. The same is true for money received as a judgment on any other civil lawsuit. If parents/grandparents fail to provide special needs language in their own estate planning documents, their bequest to a disabled heir would disqualify government benefits unless assigned by the recipient to a self-settled needs trust. Or a marital divorce could result in a lump-sum award of money or assets to someone eligible to receive Medicaid assistance. Suppose the person is disabled or mentally incapacitated when they receive the assets. In that case, the self-settled trust may be established by a person authorized by a properly drafted and executed power of attorney. If there is no power of attorney, then court approval may be necessary for an incapacitated person to establish a special needs trust.

Self-settled special needs trusts in Florida are different from third-party trusts in three respects. First, only disabled persons under the age of 65 may create a self-settled needs trust. Third-party special needs trusts may be established by anyone at any time regardless of the beneficiary’s age. Secondly, self-settled special needs trusts must be irrevocable; the disabled trustmaker cannot change their mind and either amend or undo their trust. Third-party trusts, contrarily, may be amended or terminated at any time and for any reason by the third-party trustmaker. These trusts are easily updated if there are changes in the law or family circumstances. Third, self-settled special needs trusts must include a payback provision whereby all money remaining in the trust at the disabled trustmaker’s death is paid back to the state government to the extent required to reimburse the state for Medicaid benefits paid to the trustmaker during their lifetime.

There is a type of self-settled trust called a “pooled trust” that alters the payback requirement. A pooled trust holds a pool of multiple individuals’ self-settled trust assets. An individual’s contribution is accounted for in a sub-trust account, but all the sub-trusts are managed collectively by a nonprofit professional trustee. A master pool trust may have hundreds of self-settled trust accounts. When an individual contributor dies the assets in their special needs trust account may, at the beneficiary’s option, be paid back to Medicaid or held in the pooled trust for the benefit of other pool trust members who have otherwise run out of support money. A pooled trust also can be used to isolate an applicant’s income from Medicaid eligibility. Self-settled special needs trusts are a relatively recent Medicaid planning tool. Before January 2017, these trusts were not recognized by Medicaid law, and only third-party special needs trusts could protect assets in trust for the benefit of a disabled beneficiary. Do not be confused by something written before January 2017 that says self-settled special needs trusts are not allowed. Congress since passed a law that authorized these trusts.

Here are some things to keep in mind when considering a self-settled special needs trust:

- Consider alternatives to self-settled needs trusts such as investing in a homestead property that is not a countable Medicaid asset.

- If a person can obtain satisfactory private health insurance, they are better off with an Obamacare policy than Medicaid because there are no payback requirements. Medicaid is the last resort.

- A self-settled special needs trust should utilize a professional trustee because mistakes in trust administration have large monetary consequences for the beneficiary otherwise eligible for Medicaid benefits.

- Do not confuse a special-needs trust with other types of trusts used in Medicaid long-term care planning. Florida special needs trusts isolate assets from the asset ceilings for Medicaid eligibility. There is another type of irrevocable trust that is solely designed to isolate an applicant’s income from Medicaid’s income ceilings. These “income trusts” are referred to as “Medicaid Trusts” or “Miller Trusts” and are discussed elsewhere on this website. The Medicaid or Miller Trust is established by the Medicaid applicant before entering a skilled nursing facility for the purpose of holding income above the Medicaid income ceiling in a trust. This type of trust does typically not hold or administer assets.

- Special needs trusts are complicated legal documents. Mistakes in drafting a trust document may have serious economic consequences for the intended trust beneficiary. Special needs trust agreements should be professionally prepared by an experienced elder care or asset protection attorney.

ABLE Financial Accounts

ABLE accounts are a financial tool that Congress created to ease financial strains faced by disabled individuals. The ABLE account provides for tax-free growth of qualified financial investments for the benefit of disabled persons. ABLE financial account legislation is codified under Section 529 of the Internal Revenue Code, the same Code section that provides for tax-deferred college savings plans. The ABLE accounts make tax-free savings available to cover qualified expenses, including education, housing, and transportation. ABLE accounts supplement, by may not supplant, benefits paid through private insurance, Medicaid, or SSI, and other sources.

Taxation of ABLE accounts is like a Roth IRA or a college savings 529 plan. Contributions are made with after-tax money. The funds in the account may be invested, and the amount of appreciation is tax-free. The total annual contributions to an ABLE account by all participating contributors, including family and friends, is $14,000 per taxable year. The total amount of annual contributions over time is subject to each individual state’s limits for their own 529 college savings plans.

ABLE accounts are available only for individuals with significant disabilities with an age of onset before 26. The account must also be established before age 65. The beneficiary need not be under 26 years of age when the ABLE account is set up. Still, the beneficiary must have had an age of disability onset before their 26th birthday.

There are further account limits for disabled individuals receiving SSI. The first $1000,000 ABLE account balance is exempt from the SSI individual resources limit. When an ABLE account grows to over $100,00, the beneficiary’s SSI cash benefit is suspended until the account falls back below $100,000 either from disbursements or decreased market value of account assets. The beneficiary’s eligibility for SSI cash is suspended but not lost if the account exceeds $100,000. The ABLE account balance does not affect the beneficiary’s ability to receive Medicaid assistance.

ABLE account balances are subject to “payback” similarly to self-settled Medicaid income trusts discussed above. This means that the state Medicaid agency gets paid back from the account balance at the beneficiary’s death for any amounts the state paid for the beneficiary’s care after the ABLE account was established.

ABLE account legislation is enacted at the state level pursuant to federal mandate, and the rules differ among states. For instance, the Florida ABLE United program states that only in-state Florida residents are eligible to open Florida ABLE accounts. Other state’s ABLE programs accept applicants from foreign states, and Florida residents may enroll in any state’s program.

ABLE accounts offer advantages over other types of disability planning tools such as special needs trusts. The costs of setting up an ABLE investment account are substantially less than the costs of creating a trust. The ABLE account owners can control the funds and investments directly without relying on a third-party trustee.

Sign up for the latest information.

Get regular updates from our blog, where we discuss asset protection techniques and answer common questions.